One big component of world culture, and certainly of African culture, in ancient times and in the present, is the sharing of wisdom through proverbs. Proverbs can be defined as a wise or profound sayings that often require interpretation and that express effectively some common place truths or common thought of a people. In the Christian Bible, there is a book known as Proverbs. Similarly, within the cultures of many African groups, proverbs are a prominent feature.

Proverbs of the Akan people

The culture of Akan people of Ghana and Cote d’Ivoire are no different in regard to the use of proverbs. In fact, proverbs are a common feature in past and present Akan culture. One might wonder – what are the kinds of sayings that Akan people use proverbs for? When Akan people use proverbs, what topics are referenced, and what is the content of those topics? That is the subject of this article.

As one would imagine, the sayings in Akan proverbs refer to many things in life. In order to get a better understanding of these references for a particular time in history, I accessed the collection of Akan proverbs that Robert Sutherland Rattray compiled during his time as a British anthropologist among the Asante people in Ghana. His book, Ashanti Proverbs, was published in 1916, and it features the proverbs that the people of Asanteman commonly used at the time.

For this reason, it is important for me to mention that the proverbs I will discuss from Rattray’s book Ashanti Proverbs have a historical context. They are a snapshot of Akan culture in Asanteman as far as proverbs are concerned. Having said that, these proverbs give us a rich source of culture, as well as insight into Akan culture.

When the people in Asanteman used proverbs at the time Rattray recorded them, what did they use them for? Well it turns out that Rattray created a number of classifications for the proverbs he catalogued. All in all, his book features 830 proverbs put into 14 categories. These 14 categories make up the 14 chapters in the book. Each chapter discusses a different facet of Akan life and the proverbs that are associated with that aspect.

Knowledge embedded in Akan proverbs spoken a century ago

For this article, I shall discuss the content of the first 13 chapters of Rattray’s book. For these chapters, Rattray clearly outlines categories for the proverbs he collected. For that reason, they are straightforward to discuss. Of the 830 proverbs in this book, the first 701 proverbs fall under chapters 1 to 13. The 14th chapter, titled “General precepts and maxims”, is just that. This means that the proverbs in this chapter were not put into any category and were in their own general category. They make up the last 128 of the 830 proverbs.

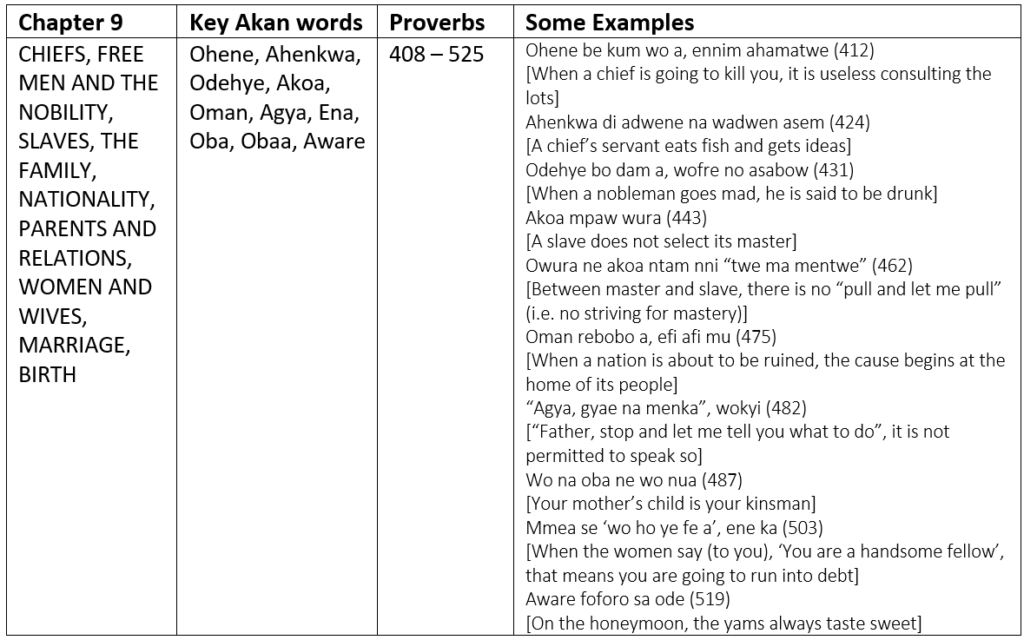

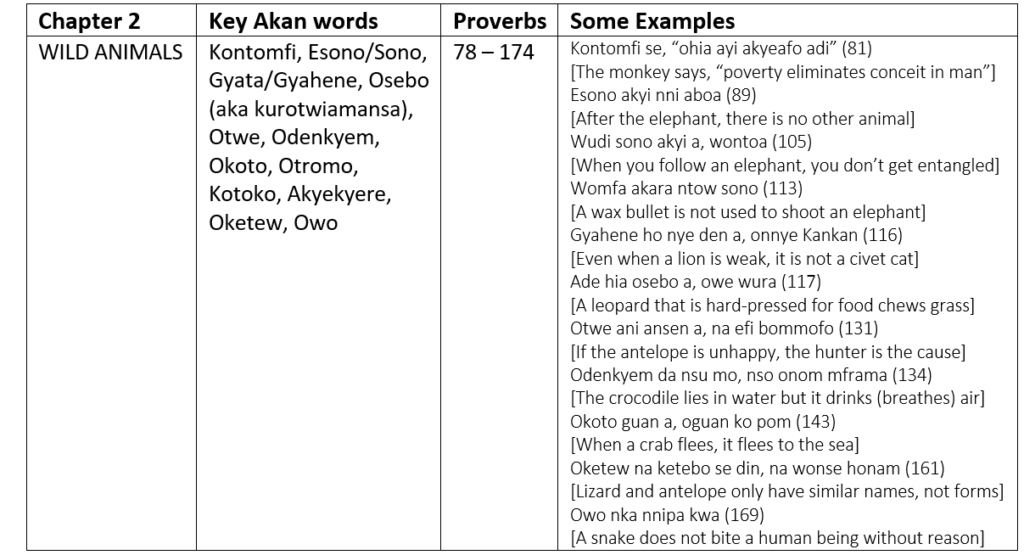

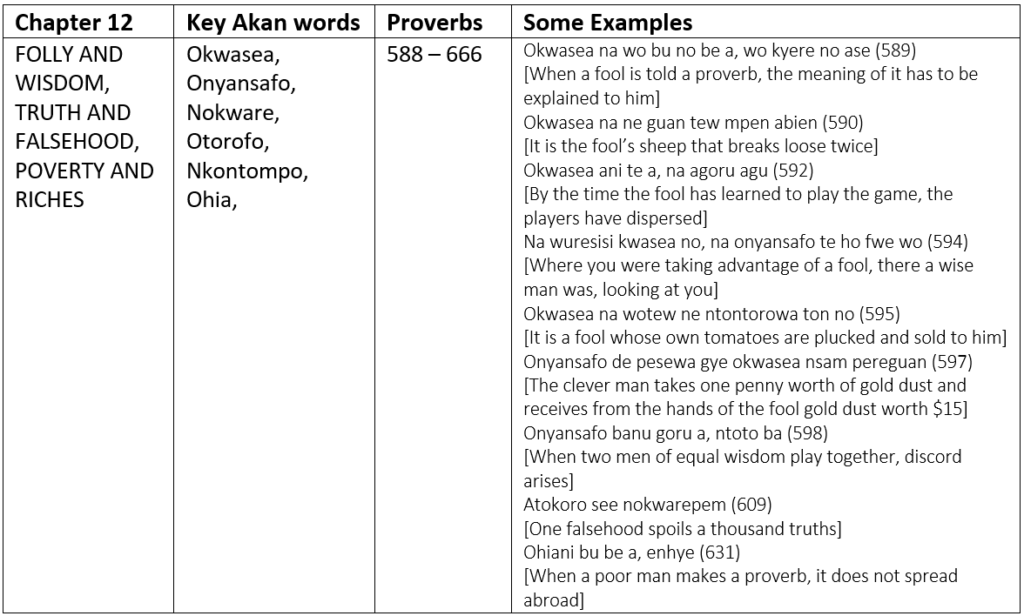

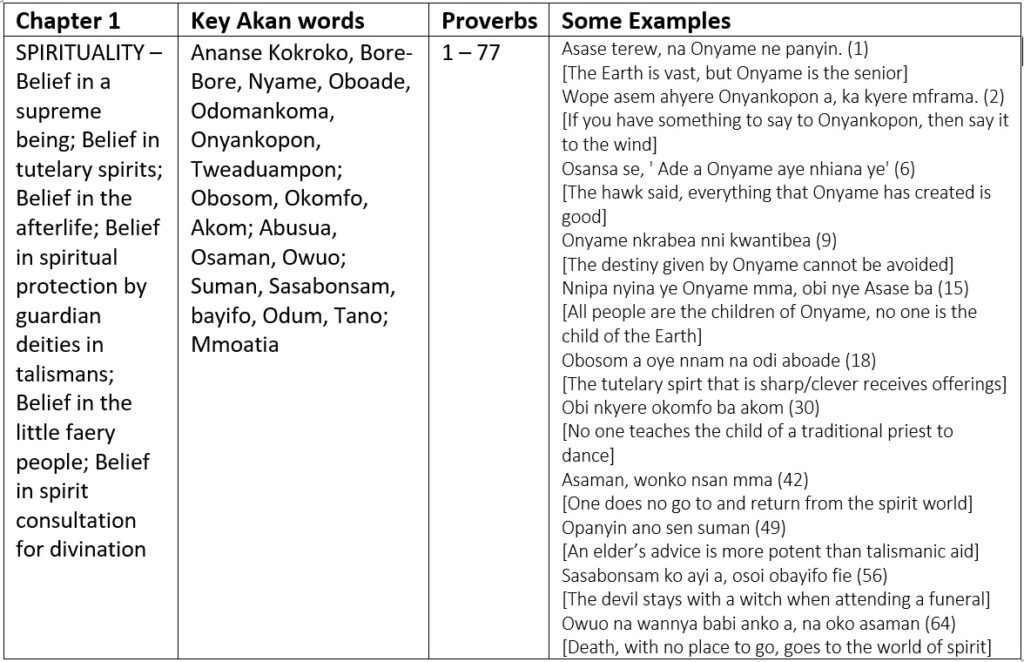

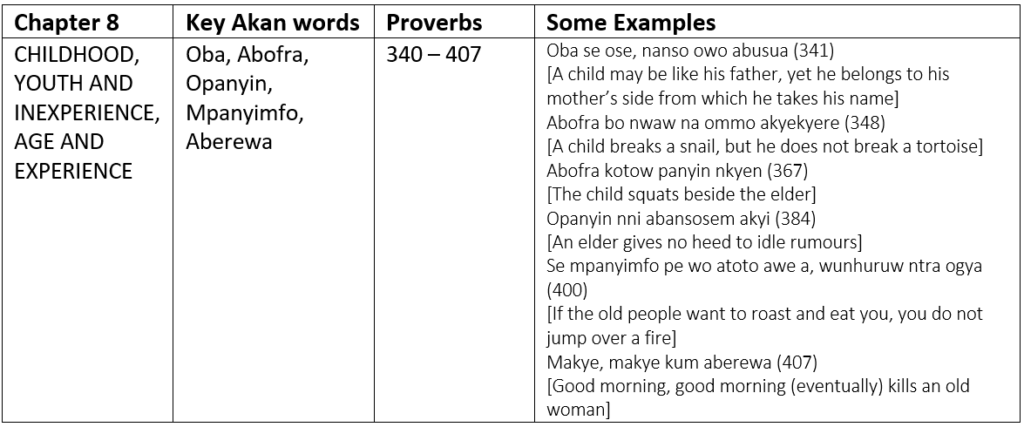

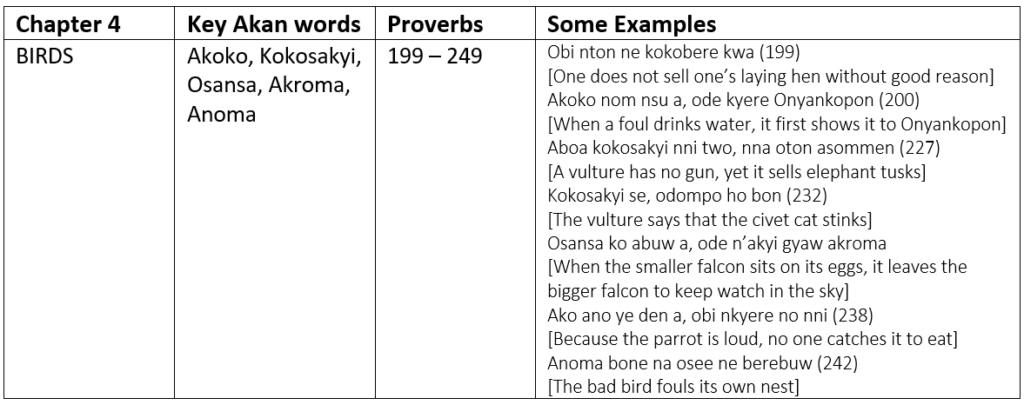

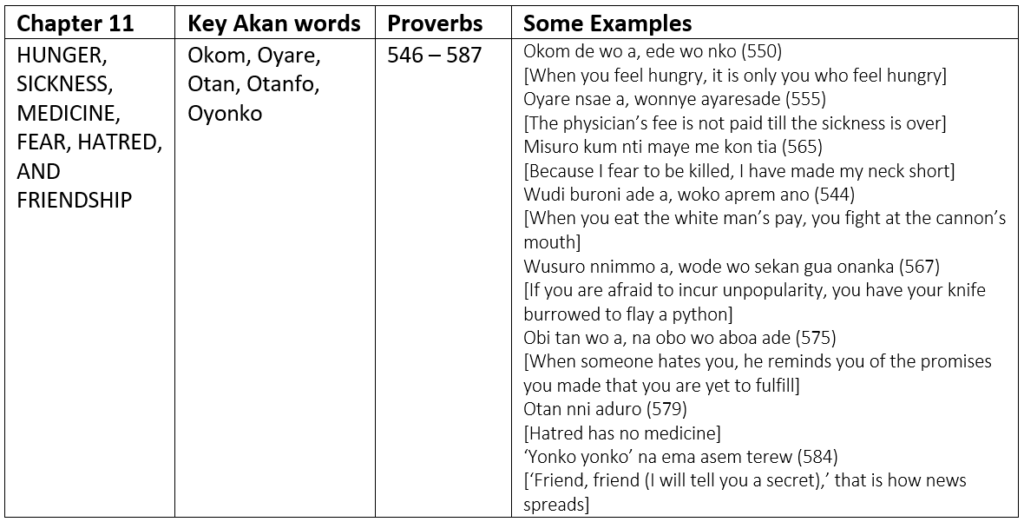

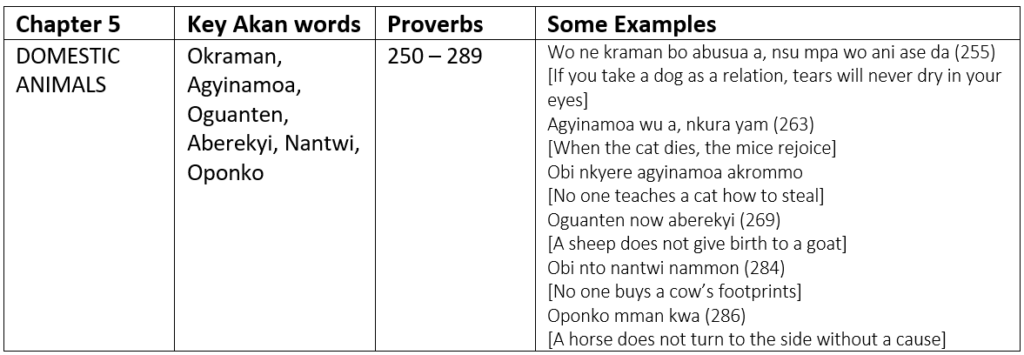

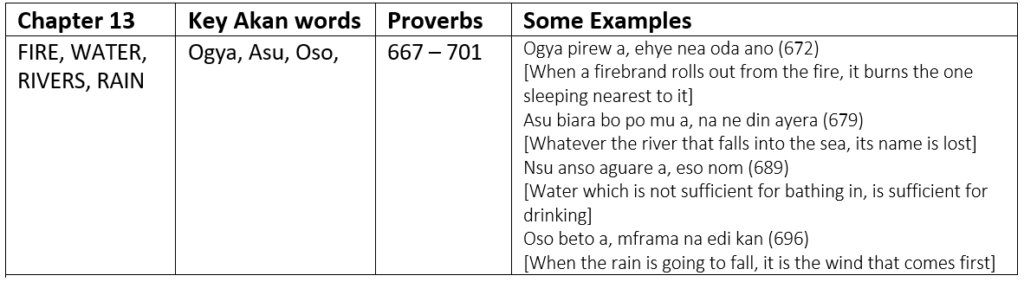

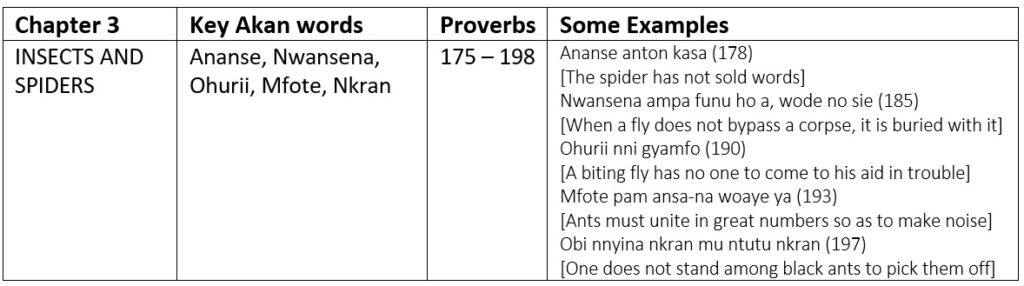

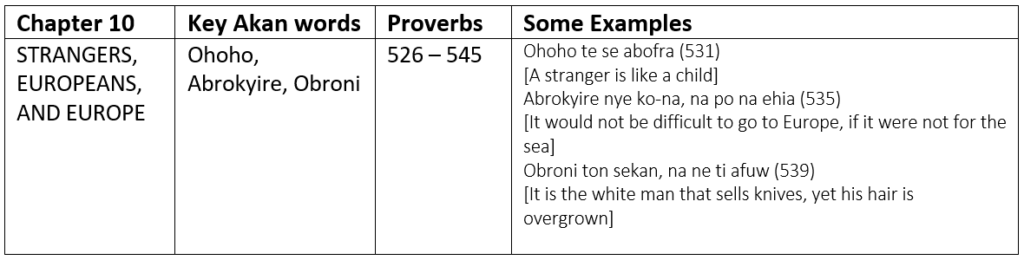

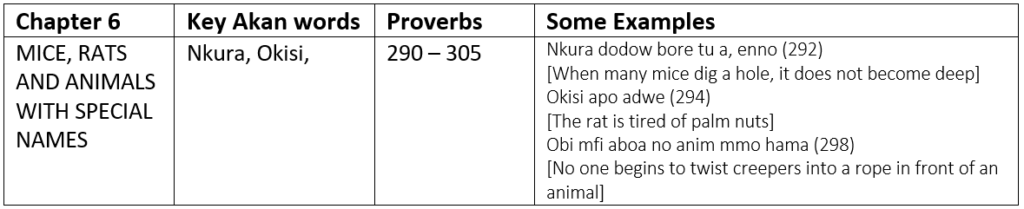

So, what aspects of Akan culture and life do the first 13 chapters touch on? Chapter 1 is about spirituality, that is, belief in a supreme being, in tutelary spirits, in spiritual protection from guardian deities through the use of talismans, in the little faery people (the dwarves/“mmoetia”), in spiritual divination and in the afterlife. Chapter 2 is on wild animals, chapter 3 on insects and spiders, chapter 4 on birds, chapter 5 on domestic animals, chapter 6 on rodents, chapter 7 on war, fighting, hunting, guns and weapons, chapter 8 on childhood, youth, age, experience and inexperience, chapter 9 on chiefs, free men and the nobility, slaves, the family, nationality, parents and relations, women and wives, marriage and birth, chapter 10 on strangers, Europeans and Europe, chapter 11 on hunger, sickness, medicine, fear, hatred and friendship, chapter 12 on folly and wisdom, truth and falsehood, poverty and riches, and chapter 13 covers fire, water, rivers and rain.

As is evident from the description of each chapter, there was a wide range of activities in the lives of the Akan people of Asanteman for which proverbs were the subject. This is still true, as we know that speaking in proverbs is still a norm among Akan people, not only among the Asante. A natural question to wonder is, for which areas of life did Rattray report the highest number of proverbs? This can easily be determined by looking at how many proverbs each chapter featured. Why is this important? Because while reading his book, some chapters have a lot more proverbs than other chapters, leading me to think that these chapters reflect areas of greater prominence in the knowledge and in the lives of the Akan Asante people.

By using this methodology for determining the “prominence” of the content of chapters based on number of proverbs, and taken as a sample of the collective knowledge of one group of Akan people, I am making a loose assumption that “more proverbs” means “more prominent area in the knowledge and life of the Akan Asante people”. Of course, it could also be an arbitrary quirk of Rattray’s mind that he chose to represent more proverbs for specific chapters because he had more of those proverbs, with no necessary link to prominence. However, as I read his book, I got the sense that the content of certain chapters were of greater prominence, and others were less prominent. For example, when it comes to statehood, its processes and components (the content of chapter 9), the knowledge of the Akan Asante people was most prominent in this area, with the greatest number of proverbs among the categorized chapters. On the other hand, when it comes to mice, rats, and animals with special names (the content of chapter 6), the Akan Asante people was least prominent in this area, having the least number of proverbs among the categorized chapters.

Therefore, with this basic method of demarcating the content of each chapter on the basis of prominence, I shall now describe and summarize the content of each chapter, starting with the most prominent, and ending with the least. I shall leave out chapter 14, since this chapter contains proverbs not categorized into any particular body of knowledge.

Delving into the content of each chapter

Of all the chapters in the book, chapter 9 featured the highest number of proverbs. This should perhaps not come as a surprise. The proverbs in chapter 9 center round processes in the adult social life of the Akan community of Asanteman at the turn of the 20th century. These are proverbs about the different components of a hierarchical society (chiefs, nobility, free people, and slaves). This chapter also features proverbs about family and community (parents and relations, women and wives, marriage and birth). In short, the proverbs in this chapter are about the social process that involve both men and women in Akan culture. It is about the social processes that pertain to nationhood, or if you will, “kingdomhood”, or “empirehood”. So, again it should come as no surprise that this chapter had the highest number of proverbs. Below are examples of the content of this chapter.

Following chapter 9 that centers round nationhood, chapter 2 has the next highest number of recorded proverbs in the book. This is a fascinating chapter about all the wild animals that the Akan Asante people interacted with and learned from. Given that Asanteman was in the heart of the forest, and also given that in the forest, there are so many different kinds of animals, all with unique features, this result should not be surprising. One of the great values of this chapter is that it shows how the Akan Asante people (and presumably other Akan and African people as well) learn life’s truths and lessons by observing the behaviour of wild animals, who display their own forms of intelligence. Wild animals have a natural way about them. They behave by instinct, but in ways that preserve their own survival. For this reason, their behaviour encodes knowledge that can be observed in action. A lot of this knowledge came from hunters. The Akan and other African are among the people who have learned directly from nature, and nature is the best teacher there is. Below are examples of the content of this chapter.

Next up is chapter 12. Chapter 12 can aptly be called the “wisdom” chapter. It deals with folly, wisdom, truth and falsehood, poverty and riches. I thoroughly enjoyed this chapter and I laughed so much on several occasions while reading the proverbs in this chapter. The Akan people are wise indeed. For those who know the Akan folktale of Kwaku Ananse, who wanted to steal all the knowledge of the world to keep for himself, but failed, this chapter is for them. Very deep, insightful precepts and maxims, and I found them funny because the truth embedded in these proverbs still rings very true today. This is even as it has been over a century since the book was written, and even when Akan society has been transformed in modern ways. Here is a summary of this chapter.

Closely behind chapter 12 in prominence is chapter 1. In fact, chapter 1 had only one proverb less than chapter 12, in Rattray’s compilation. By my method of determining prominence, I would conclude that chapters 12 and 1 are virtually of the same prominence, since the difference of only one proverb makes the difference between the two virtually insignificant. Chapter 1 is about spirituality. Specifically, it is about the belief in a supreme being, in tutelary spirits, in spiritual protection from guardian deities through the use of talismans, in the little faery people (the dwarves/“mmoetia”), in spiritual divination and in the afterlife. For me, a main takeaway is that, considering that these 701 proverbs serve as a sample of the knowledge of the Akan people, and taking into account that chapters 1 and 12 are of virtually equal prominence, one could surmise that among the Akan Asante people of a century ago, equal value was given both to wisdom pertaining to mundane life and to wisdom pertaining to spiritual life. If we can make that conclusion based on the assumptions of the methodology I have adopted, then that is telling indeed. Now, we can have a look at a summary of this chapter.

After chapters 12 and 1 comes chapter 8. This chapter is about childhood, youth and inexperience, age and experience. In other words, this is a chapter about the stages of life an individual goes through, not only in Akan societies but in all societies. In all societies, there are younger people (many of whom tend to be inexperienced), and there are older people (many of whom tend to be experienced). So, this chapter takes the number five spot. In contrast to chapter 9, which had the greatest number of proverbs and is the chapter about “adults”, chapter 8 is the chapter about the youth and the aged. Malidoma Some wrote in his book Of Water and the Spirit (and I paraphrase) that the youth and the aged have something in common because both groups are close to the world of the ancestors, with the youth having recently arrived from the ancestral world an the aged on their way there. So, chapter 8 is an important chapter that complements chapters 9 and 12 in the knowledge about human beings, about people and about society. Let’s have a look at a summary of this chapter.

Moving on, chapter 4 is next. This chapter is about birds! Now, one might think, of all the animals there are, why will a chapter about birds be the most prominent chapter for one specific group of animals? Well, I guess it is a good question. I shall venture some speculation here, for your consideration. First of all, on a totemic level, birds are important in Akan society. Why? The Akan people have seven standard clans (some groups have had 8 clans in the past). Out of these 7 clans, 4 of them have birds or bird-like creatures as their clan totems. These are the Agona clan, with a parrot as its totem, the Asenie clan, with a bat as its clan totem, the Asona clan, with the crow as its clan totem, and the Oyoko clan, with a falcon/hawk as its clan totem. These totemic creatures serve as primordial teachers and guides. Of course, with the Oyoko clan, and its falcon/hawk totem, there are also connections with the Ancient Kemetic/Egyptian deity Heru (Greek Horus). There was also the Asakyiri clan, an 8th clan that had the vulture as its totem. Apart from the totemic connection, the Akan people also have lived with several domesticated birds such as chicken, ducks, and guinea fowl. All of these animals can serve as “teachers” as they exhibit natural behaviours that display insights into life. Examples of content from this chapter are as follows:

The next chapter of prominence was chapter 11. This is the chapter about hunger, sickness, medicine, fear, hatred and friendship. So again, we are back in the realm of knowledge gained from human interactions and processes. Fascinating insights into human behaviour and human interactions in this chapter. Here is one example. The Akan proverb, “’Yonko, yonko’ na ema asem terew”. This is proverb 584 out of 701. It can be loosely translated as “‘Friend, friend (I will tell you a secret),’ that is how news spreads. This is as true as it was over a century ago as it is today. What does this mean? Imagine that you are told a sensitive secret by a friend. Your friend said to you that this is a secret, and it is about so-and-so, but that because it is a secret, you have to keep it to yourself. Don’t tell anyone. You, in turn tell your trusted friends or partners the same secret, with the same admonition, for them not to tell anyone. At this point, it is no longer a secret, because at least one of those people may end up doing the same with their trusted friends. The result is that the ‘secret’ is now no longer a secret, everyone gets to hear it in the end. Main difference is that its mode of spread and transmission may be slower than it otherwise would have been without the admonition. Here are a few more examples from this chapter:

Chapter 5 takes the 8th position of prominence. This chapter is about domestic animals. Among the domestic animals discussed in this chapter are dogs, cats, goats, sheep, cattle, and horses. Notice that Rattray did not include domesticated birds in this category, because this group is included in the chapter on birds. It is important to point out that just because this chapter is about domesticated animals does not mean that it lacks fascinating insights and knowledge gained from direct observation of animals around us. This chapter too has some profound insights to ponder. Some of its content can be found below:

From chapter 5, we arrive at chapter 13. Chapter 13 is about fire, water, rain and rivers. Again, this kind of knowledge, similar to what we saw in chapter 2, pertains to knowledge about nature. It can be thought of as the insights gained from observation of nature, outside of Akan society. Fire and water in particular are two of the “primordial elements” in nature, of which much can be written about. I would also point out that this knowledge about nature intersects and overlaps with the spiritual knowledge that serves as the content of chapter 1. Examples from the content in this chapter are shown below:

Our next destination is chapter 3. Here, the content is about insects and spiders. Now, one might be thinking, is this the chapter about Kwaku Ananse? Sorry to disappoint you. Ananse does feature in this chapter, but not as the central character in an epic folktale story. Rather, Ananse is really the name for spider among the Akan. Have a look at these examples.

Next enroute after chapter 3 is chapter 10. This is the Oburoni and Abrokyire chapter. In other words, this chapter is about what the Akan Asante people were reported to have said about strangers, about Europeans and about Europe. Really insightful proverbs, I would invite the interested reader to check them out, and of course the proverbs from all the other chapters as well. Interesting to note that of all the prominent chapters, this one appears to be one of the least. The Akan Asante of a century ago were more concerned about their own societies and about the knowledge gleaned from observing life in their own societies than they were about strangers, including Europeans. This is one of the perspectives that appears to have changed a century later, where now “Oburoni” and “Abrokyire” hold places of strong prominence in conversations and narratives. Anyway, just an observation. A few examples for here:

Finally, we arrive at chapter 6, the chapter about mice, rats and animals with special names. I initially wondered why this chapter was included. I could only surmise that Rattray attempted to be comprehensive in his coverage. Since mice (nkura) and rats (nkusie) also have a place in the conversations that occur in Akan societies, they too made it the proverbs list. I have included a few examples from this chapter as well:

Conclusion

That brings us to the end of this short investigation. So, to answer the question of what is it that the Akan people of old used proverbs for in life, one answer, based on the data set of Rattray’s proverbs lists, is that proverbs were used to share profound insights about Akan society, about the natural world and about the world of spirit. The proverbs in the 13 chapters account for a wide scope of observed life activities in these three overall arenas. Of these three arenas, the knowledge about human interactions and processes in Akan society overall was most prominent. In this article, I highlight the content in these arenas according to chapters, and briefly discuss each chapter given in Rattray’s book Ashanti Proverbs.

As an overall point, I would point out that the knowledge in these proverbs is in an “action and consequence” format. Actions and consequences are arguably the fundamental basis for any kind of knowledge in manifest reality, but that is a discussion whose scope is beyond that of this article.

This particular collection of proverbs is interesting because it was compiled over a century ago. There are other collections of Akan and other African proverbs, some contemporary and others of earlier times. It would be revealing to examine the categories Rattray gave across different collected samples of proverbs as data sets, to observe any congruence, variance or altogether different groupings of knowledge bodies as expressed through the content of the proverbs. In other words, I would like to do this sort of analysis and synthesis again with another collection of Akan or other proverbs (e.g. Hausa), or for someone else should do it, for which I would be keen to read the results.

References

Ashanti [Google scholar]

Ashanti law and constitution [Google scholar]

Article Themes: Idioms, Traditional knowledge, Indigenous wisdom, Life’s lessons